On January 20, 2018 several thousand people gathered on the capitol grounds in Des Moines, Iowa, for the”If You Can’t Hear Our Voice, Hear Our Vote,” the second Women’s March. Photo credit: Phil Roeder via Wikimedia Commons.

“History@Work” is an apt title for this blog and a metaphor for a lot of the work that public historians do. But, history seems to be getting off with light duty in the arena of public discussion these days.

Major public issues make the news every day, and, clearly, the nation is divided on an array of complex social and cultural topics related to the economy, health care, immigration, race, and gun control. In the 24/7 news cycle and high-velocity spread of news information via social media, there is an obsession with the present. Media outlets are constantly featuring “breaking news” without really understanding why things are happening. The historical dimension of major issues—their origins, precedents, parallels, and historical insights from past experience—is left out of most discussions. Listening to news commentators often seems to convey the implication that history is not relevant.

Screenshot of History Relevance Toolkit, 2018.

Historians’ skills can help here, as explained and confirmed in the History Relevance Campaign’s materials. Historians are particularly skilled at explaining the process of social and political change over time. They help people understand cause-and-effect relationships, analyze and weigh evidence, understand and confront biases and preconceptions, and discern underlying patterns in complexity. They are adept at presentations that are fair and reasonably objective; fact-based, with sources made apparent; presented clearly, for a broad, popular audience, in ways that interest and engage them; and connected in some discernible way to important current issues.

The need for clear historical analysis should mean this is a boom time for public history, with our programs—and our perspectives and insights—more in demand than ever. But that is not happening nearly as much as it should. Public historians need to be more proactive in tactfully pushing into more conversations and discussions of challenging issues. For instance:

* In the current debate about immigration, it would be useful to recall the causes and impact of such policies as the Chinese Exclusion Act (1882), the nation’s first significant immigration restriction, and the Johnson-Reed Immigration Act (1924), which limited the number of immigrants through a national origins quota; as well as how Americans have regarded immigrants over the years. (See History@Work Editors’ conversation on interpreting immigration here.)

* In the discussion of North Korea, it is helpful to recall how Korea got divided into North and South in the first place (Soviet-American antagonism after World War II was a major factor); the Korean War (1950-1953), where South Korea’s defenders were mostly Americans; and President Dwight Eisenhower’s role in ending the war.

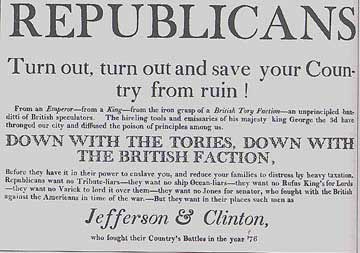

An 1804 campaign poster urging support for the Jefferson-Clinton ticket in opposition to the perceived tyranny of the Adams administration. Image credit: Monticello.org

* In discussions of “fake media” and “post truth,” it would be enlightening to understand more about the history of the First Amendment, the Sedition Act of 1798, President Lincoln’s policies toward critical newspapers, the Sedition Act of 1918, and other initiatives in history that affected freedom of speech and the press.

* There is lots of discussion of trade and tariffs these days, but very little about the politics and impact of past tariff initiatives, e.g., the Payne-Aldrich Tariff of 1909 (which raised rates and helped split the Republican Party and led to the defeat of President William H. Taft in 1912) and the Smoot-Hawley Tariff of 1930 (which raised rates and exacerbated the Great Depression).

Putting history to work to broaden and deepen people’s understanding of complex, unsettling issues might mean an expansion or extension of work that public historians are already doing. It might be something new, which requires innovation, experimentation, and improvisation. Whatever is undertaken would need to be consistent with program mission and realistic in terms of available resources. The work would need to avoid slipping into the role of pundit or reinforcing partisan positions. We also need more discussion of how connecting with current events could be used to raise the visibility of and support for public history programs.

This post is meant to be a very modest suggestion for a conversation about boosting our visibility, currency, and relevance. Hopefully that would be a conversation worth having in the public history community at this critical time in our nation’s history.

~ Bruce W. Dearstyne holds a BA in history from Hartwick College and a PhD in History from Syracuse University. He has taught U.S. and New York State history at SUNY Albany, SUNY Potsdam, and Russell Sage College.